Far from being “hidden figures,” women have been working in computing since the earliest days of the new field. Unlike their male counterparts, however, they’ve often faced gender bias and discrimination in their own families, schools, and the workplace when pursuing their interest in mathematics, science, engineering, and technology. But they’ve always been there, in plain sight, for those who look for them.

Meet some amazing women from across the decades who share moments of their lives in computing and technology—from childhood to college, from their first job with computers through the ups and downs of their careers, and to the wisdom that comes with success, failure, and time.

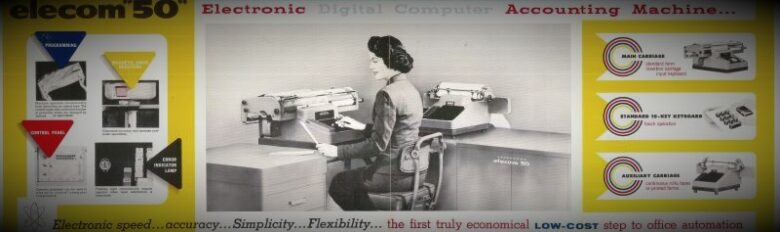

Part of the cover of a 1958 IBM publication, The World of Numbers.

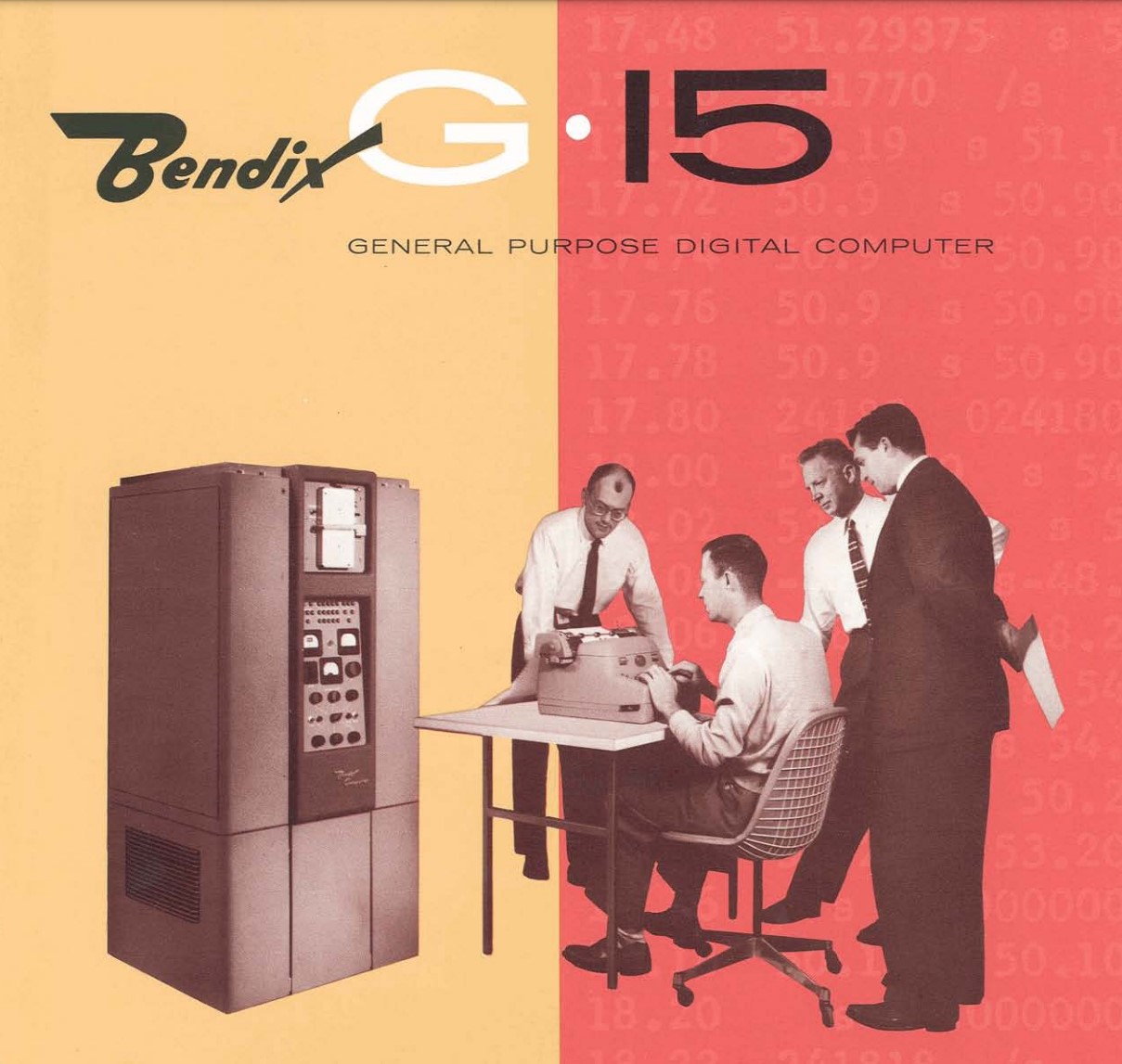

An early interest in math, science, solving problems, and sports—particularly baseball—are recurring themes in the oral histories of tech-minded women. But American culture in the 1930s, ’40s, 50’s and beyond did not often portray women as mathematicians and scientists. Early computers were the domain of the government, large corporations . . . and men.

1955 brochure produced by the Bendix Aviation Corporation. Note the absence of women in the photo. Visit the collection to see the full brochure.

Girls were steered toward careers as teachers or nurses, but sometimes family members or a special mentor encouraged them to pursue their interest in math or science.

“We were all good in math in my family. So the fact that I was good in math wasn’t particularly noted,” says Jean. What was noted was her youthful talent as a pitcher. She remembers:

“I was quite a star. So there used to be stories about me in the newspaper. And when I would go to town with my mother, people would stop me on the street, particularly men, and tell me what I’d done wrong in the last game and how I should do things.”

Born Elizabeth (Betty) Jean Jennings in 1924, Jean was one of the original six programmers for the ENIAC computer and thus one of the first computer programmers in the world. She’s on the left in this photo.

Check out the collection to learn more about the photo. See Jean’s oral history.

Born in 1925, Evelyn became interested in physics when she started reading her older brother’s Astounding Science magazines and science fiction books from the library. She says:

“I remember going to my science teacher in junior high and asking him about something I had read. It was the idea that when something goes very fast, close to the speed of light, it gets smaller in the direction of the movement (the Lorentz contraction). So I asked him about this, and he said, ‘Oh no, that’s not science. They’re making it up.'”

But after graduating from high school at 15, Evelyn went to college and learned her teacher had been wrong. She later earned an additional degree in physics and became a renowned computer designer.

CHM has a fun collection of science fiction books. See Evelyn’s oral history.

Margaret was born in 1936, and math was her favorite subject. She says, “What I did not like was Home Ec, because girls were supposed to take it.”

Margaret became a computer programmer and led the software team that put men on the moon. In this iconic photo, she’s standing beside a tower of printouts of Apollo Guidance Computer source code.

Read more in this blog. See Margaret’s oral history.

Women interested in math, science, and engineering often faced the bias of male professors or constricting college rules when they sought out higher education in the fields they cared about. Some of their fellow female students seemed to be more focused on finding a husband than on getting a degree, according to computer scientist Phyllis Fox, who attended Wellesley in the 1940s.

A selection of technical books from CHM’s extensive collection.

Lois Britton, cofounder of the iconic Whole Earth Catalog, loved to take things apart to see how they worked, but she decided not to pursue a career in engineering in the 1960s.

Lois earned a degree in math. Other women got creative about overcoming barriers.

Ann’s college advisor in the 1950s was the chair of the chemistry department, but he wouldn’t let her major in it. He said, “Women in advanced chemistry labs are too distracting.” She came up with an ingenious way to get the education she wanted.

Ann went on to develop pioneering time-sharing software that made it easier for students (and professionals) to use computers for their work.

Learn more about time-sharing systems from a vintage GE brochure. See Ann’s oral history.

Growing up in Soviet Armenia, Joanna decided to be a physicist at the age of five when she read a biography of Enrico Fermi. After emigrating to the US, she switched high schools so she could study physics, and she went to MIT in the 1970s. She says:

“At MIT, I just felt free to be whatever and however I wanted to be. And I was like a kid in a candy store. I wanted to take every class.”

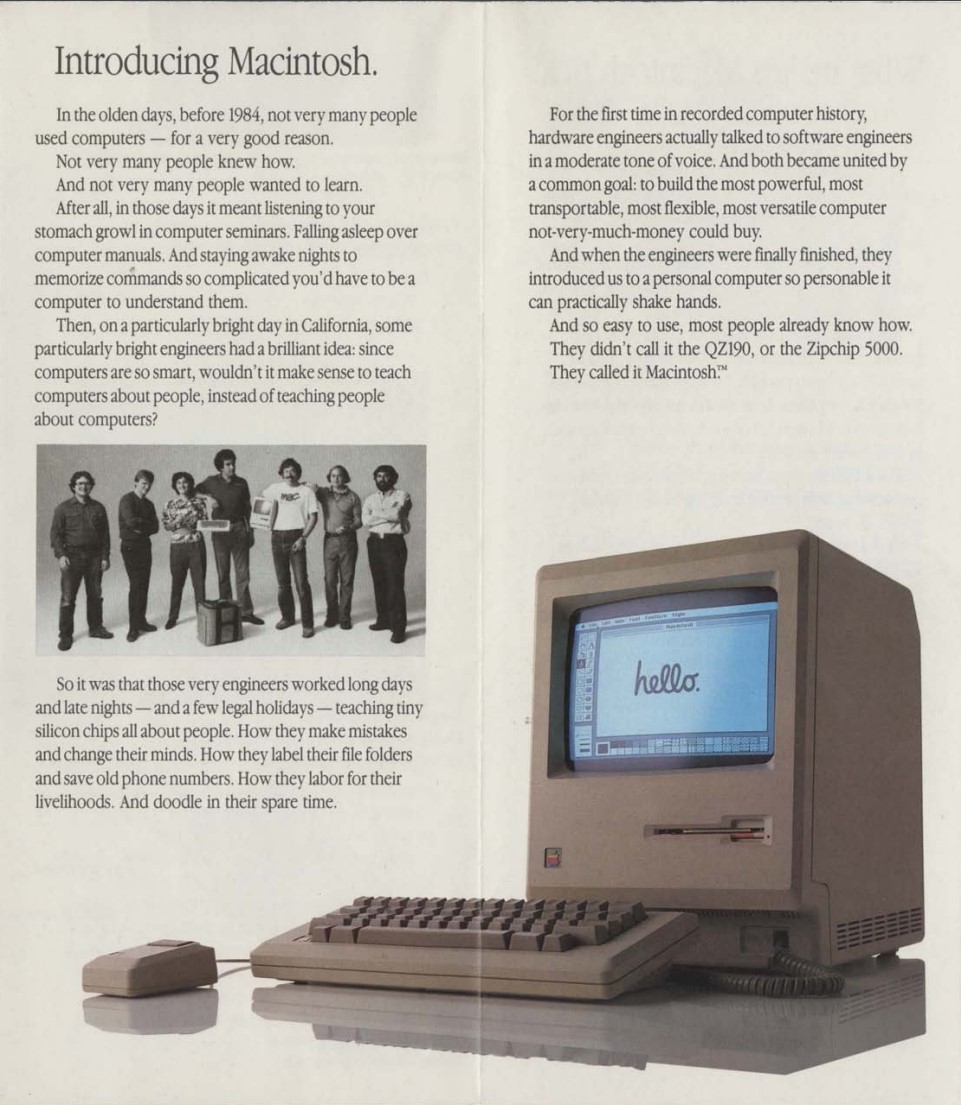

Joanna became friends with the students who hung around Marvin Minsky’s storied artificial intelligence lab, learning from them “by osmosis.” She went on to become a key member of the Macintosh team at Apple.

Minsky developed the robot arm in the photo in 1968, the same year Joanna came to the US. See her oral history.

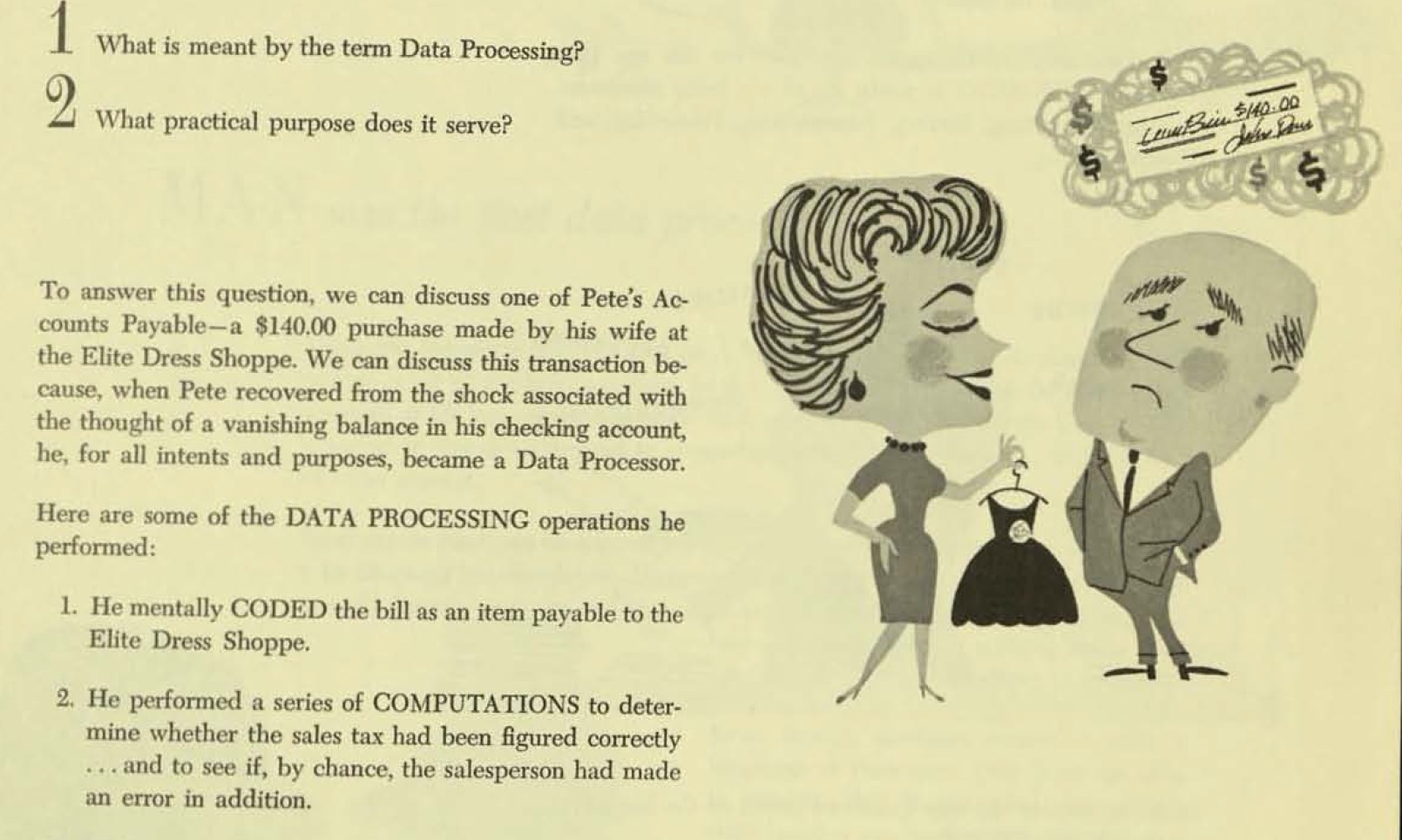

As they entered the workforce, young women who had earned degrees in STEM fields—science, technology, engineering, and math—gravitated toward jobs that would allow them to use their knowledge. And, they fell in love . . . with computers. But even when that sector was new, they faced sexism and bias.

A woman is portrayed stereotypically on this page from a 1960s booklet on data processing from NCR (National Cash Register Company). See the full booklet.

Sometimes, however, new technology provided new opportunities for women—to learn skills, to start businesses, and to imagine different ways to communicate.

Ann passed IBM’s Programmer Aptitude Test in 1956 and was hired as a System Service Girl, today’s System Engineer. Located on a busy corner in Manhattan, the company had set up a new 705 computer in the window so people could see what a computer looked like. Ann remembers:

“Now, the good news about being a woman—[for] once, there was good news—is that they wanted to make it look easy to use a computer. And so, the women got to do all their debugging and testing on the 705 downstairs. And since there were almost no women in the class, we really had great access. For being on display in the window.”

Check out items from the collection to see an IBM brochure for the 705, Ann’s full oral history, CHM’s extensive collection of 705 materials, and a 1968 NCR programmer’s test. Could you have passed?

Known as “St. Jude,” Jude was born in 1939 and became a self-taught programmer and advocate for civil rights and women in computing. In 1973, she and other hackers created Community Memory in Berkeley, California, a computerized bulletin board that was one of the first public computer network systems. Anyone could post messages on the terminal, which was connected to a mainframe timeshared computer.

Milhon pointing to a computer at the Community Memory Center, 1988-1990. From the CHM collection, 102774057-03-01

The counterculture saw computers as tools in service to corporate and government power. Providing everyday people with access to the machines was a radical act.

Explore Community Memory in the CHM collection below.

In the early 1980s, Mary combined two of her own interests to show people how to use their personal computers, like the Apple II, for managing their gardens. Her Landscaper software selected all the right plants, and for people who didn’t have a green thumb it promised to save time and eliminate costly mistakes.

By 1986, Mary’s software was called CompGarden and she was producing a newsletter, The Online Gardener, to field questions about gardening programs and covering topics like “Tracking Insect Activity Using a Home Computer.”

See a 1983 brochure for Landscaper software and a 1986 issue of The Online Gardener.

As they explored their roles as engineers and computer scientists, women in tech experienced the highs and lows of daily work life. They forged their paths in a sexist culture that often devalued women even as they joined the workforce in greater numbers.

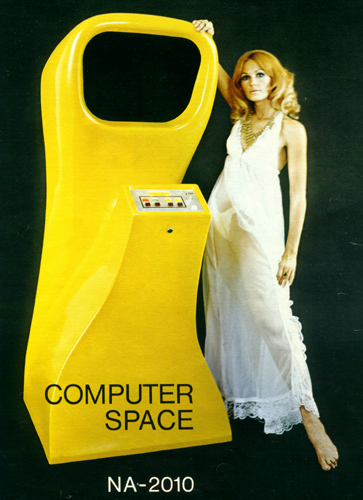

This sexist advertisement for a game called Computer Space appeared in magazines c. 1972. Learn more.

Sometimes women found that the best way to meet their potential was to start an entirely new company.

By 1960, Evelyn had extensive experience with computers. Working at Teleregister, she had designed an airline reservation system, one of the largest computer systems at the time, as well as the first computerized banking system. When she applied for a job at the New York Stock Exchange, she was hired immediately. But she never worked there. Evelyn recalls:

“The Stock Exchange Manager called me a few weeks later, and said, ‘I need to talk to you.’ . . . And he said that the Board said that they could not hire me. Why? At the time, I was probably one of the very few people in the world who could do this job. And he said to me, ‘They said that you’re a woman, you’d have to be on the stock market floor from time to time. And the language of the floor is not for a woman’s ears.’”

At the age of 45, knowing she wouldn’t go anywhere at Teleregister, Evelyn founded Redactron in 1969 and made herself president.

See a Teleregister brochure, including the schematic of its reservation system. Learn more about Evelyn’s early word-processing company in the Redactron IPO.

Hired by IBM in 1959, Fran became an expert in optimizing compilers. She was assigned to work on Harvest, a code-breaking project for the National Security Administration (NSA) on the Stretch computer. Fran worked with a program called Alpha, and her assignment was to write the acceptance test for it. She says:

“I knew that I couldn’t leave Fort Meade until that was done and I dreaded it for the whole year I was there.”

Fran was at Fort Meade during the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962. She remembers all the computer printers draped with black cloth so people couldn’t see what was going on and there were Marines everywhere.

Learn more about the Stretch/Harvest in this document created for a reunion. See Fran’s oral history.

After finding out her salary was less than half that of the men she was training, Ann left IBM in 1966 and took a job at a new company called Tymshare. Although she wrote the code for their time-sharing computer, her boss believed her husband was behind her success and hired him as a manager. They also gave her fewer stock options than male employees because “it would be immoral to tempt a woman to continue to work instead of stay home and have children.” Ironically, when she had just given birth to her daughter, Ann recalls:

“And by three o’clock the next afternoon, I’m still lying in the hospital. Dave calls. Dave Schmidt calls. He said, ‘Our best customer has one more feature they want in the operating system. Could I bring a terminal over?'”

Ann eventually became the first woman vice president of Tymshare. When it was bought in 1984, she left to found KeyLogic and then Agorics.

See the above image of a young woman working on a Tymshare terminal in the collection.

Margaret started working at MIT in 1959. From there, she went on to key positions in important government research projects. She was one of the few women who worked with the machines that were largely a mystery to the general public. Her career vividly illustrates the uses to which computers were put during the Cold War.

Many talented women in tech fields achieved significant technical and career milestones, despite the ongoing dominance of men in the field.

In this 1984 advertisement for the new Macintosh personal computer, Joanna Hoffman is the only woman pictured with the Apple team. See the full brochure.

Among many other honors, Fran Allen was the first woman to receive the coveted Turing Award in 2006, the most prestigious award in computing. Margaret Hamilton received the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest civilian honor in the US, in 2016. Evelyn Berezin was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame in 2020. All are CHM Fellows.

For a woman entrepreneur, leading her company to an IPO (initial public offering) sent the message that she’d made it in a man’s world. Hardware pioneer Lore Harp McGovern and software pioneer Sandra Kurtzig were the first women founders on the NASDAQ, and both companies went public in October 1981. Below are their stories.

Women who forged careers in tech in the 1950s, ’60s, ’70s and ’80s knew that they were unusual, and they hoped to serve as role models for future generations.

What would the world look like if women had roles equal to men? Anita Borg, founder of the Institute for Women in Technology, had this to say in 1997, and her vision is still fresh today.

Anita Borg, Women and the Future of Technology, 1997

Watch the full video.

Women in Computing: The Management Option, Panel Discussion. (video)

Women in the History of Computer Science, Panel Discussion (video)

Patricia’s Perfect Pull (blog)

Women’s Work (story)

This story was supported by a generous grant from the Kapor Center, along with five related events and a series of ten oral histories with BIPOC computing pioneers.