June 1968, I checked in at the lobby of the Fairchild R&D facility on Miranda Drive in Palo Alto. A distinguished gentleman with a huge grin rushed towards me and, energetically pumping my hand, greeted me like long lost friend. “David, it’s so good to see you!”

I glanced at the name on his employee badge. “And you too, Harry.” Having no recollection of seeing him before, I asked, “It’s been a while. Remind me where we met.”

“I don’t think we have. But Bonifacio sent me a telex saying you were moving here and to look after you.”

I had just transferred to California from the UK, where I worked for SGS-Fairchild, the European affiliate of Fairchild Semiconductor. Harry explained that he had installed the silicon manufacturing process in the SGS factory in Italy and still kept in touch with the managers there.

Harry Sello continued to “look after me” just as he befriended and looked after countless others who passed through his enthusiastic, smiling orbit during his 60-year career in the semiconductor industry as the “Valley of Heart’s Delight” morphed into “Silicon Valley.”

Harry was born in born in 1921 in Chernihiv near Kiev, Ukraine, but then, in Russia. Carrying only the ancient family samovar, as Jews who had served in the Czarist army his parents fled with Harry to the USA in 1923. They settled in an Eastern European community in Chicago where his mother worked as a nurse and, although qualified as an accountant, his father delivered milk. They encouraged his interest in reading and music; he was a cellist in the high school orchestra. Sympathetic teachers mentored him in math and chemistry.

On graduating from the University of Illinois with a BS in chemistry in 1942, Harry enrolled in graduate school at the University of Missouri. With a couple of years of service in the US Navy in the Asia-Pacific theater, he earned MA and PhD degrees in physical chemistry and joined the prestigious Shell Oil Development Company in Emeryville, California, as a research chemist in 1948.

In addition to research on catalysis process development, Harry conducted live chemistry demonstrations aimed at high schoolers on the local public television station. Under the title Tempest in a Test Tube, a second series funded by the Ford foundation and recorded by WGBH was broadcast nationwide.

In 1957, William Shockley recruited Harry for his experience in physical organic chemistry to join his Shockley Semiconductor Laboratory in Mountain View. Although both Gordon Moore and Bob Noyce warned during the interview process that Shockley was a difficult person to work for, he was flattered that a Nobel Prize winner wanted him on his team.

Harry (center) with Stanford Professor James Gibbons (left), Mountain View Mayor Rosemary Stacek and Mrs. Shockley with Jacques Beaudouin (right) at the unveiling of the Shockley Semiconductor Lab plaque in Mountain View, CA, 2002. Photo: Courtesy Jacques Beaudouin.

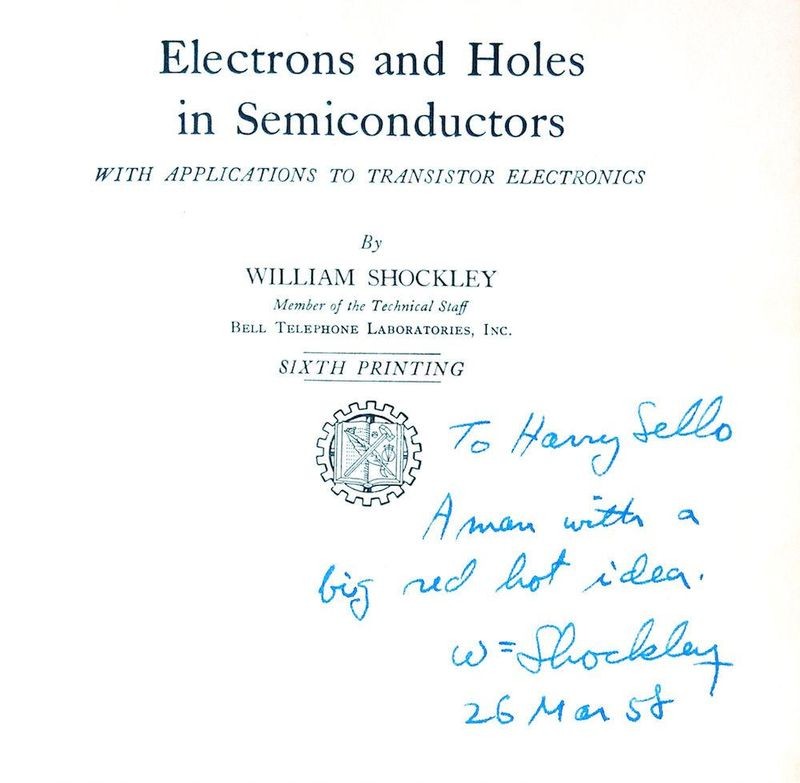

When the “Traitorous Eight” departed to found Fairchild a few months after Harry arrived, they invited him to join them, but he was not comfortable about leaving so soon. He stayed for a couple of years working on resist materials and silicon device structures. A memorable project involved constructing an efficient diffusion furnace, for which Shockley rewarded him with a signed copy of his magnum opus, Electrons and Holes in Semiconductors, inscribed “To Harry Sello, A man with a big red hot idea.” That volume is now in the Museum’s collection.

Title page of “Electrons and Holes” endorsed to Harry by the author (1958)

As an example of Shockley’s competitive, ego-driven personality, Harry liked to tell the story of their lunchtime swimming date. Anticipating a refreshing dip, after several laps of the Stanford pool, Harry hauled out to relax and was astonished when his partner continued for another 40 lengths to prove beyond doubt who was the superior swimmer.

Harry joined Fairchild in 1959 as head of preproduction engineering on silicon transistors where he worked with the team that developed the planar process. Based on this experience he served as an expert witness on integrated circuit process patent litigation with Texas Instruments that Fairchild won, resulting in substantial royalty payments to the company.

In 1960 Fairchild signed an agreement to create SGS-Fairchild as a joint venture company to manufacture and market semiconductor products in Europe. One weekend Bob Noyce turned up at Harry’s house where he was laying a tile floor. After offering advice on how to prepare the surface, he told Harry that he wanted him to catch the next flight to Italy to figure out how to proceed with the project. After Noyce agreed to take care of finishing the floor, Harry consented to leave.

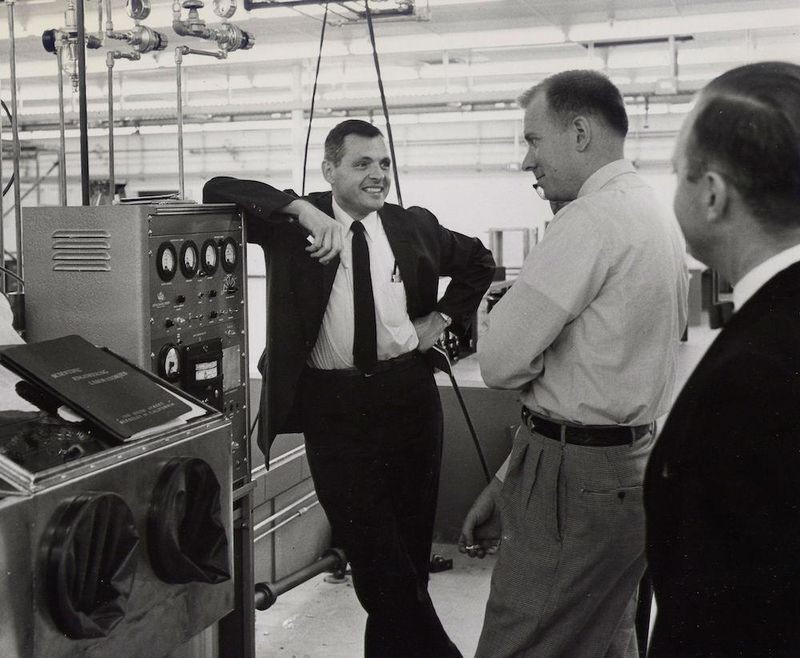

Demonstrating a new model of assembly equipment, ca.1964

This evolved into a two-year sojourn as operations manager at the factory outside Milan. One of his favorite stories about that period was that he realized his Italian had reached a certain level of proficiency when he was required to fire a supervisor for having sex in the office. The next morning the employee’s wife, unfazed by the infidelity, assailed Harry for taking bread out of the mouths of her children. He understood every oath that she threw at him. On his return to the US, Harry headed a Materials and Processes department reporting to Gordon Moore at the R&D facility where we met.

Harry’s outgoing personality, TV experience, and ability to explain complex technical matters in simple language came to the fore in 1967 when Fairchild produced A Briefing on Integrated Circuits. This video forerunner of today’s infomercials was broadcast by more than 30 stations located near major electronics customers and seen by an estimated 2 million viewers across the country. From his 20 years of fundraising as an auctioneer for KQED Channel 9, his face was also familiar to audiences around the Bay Area.

Screenshot from A Briefing on Integrated Circuits, 1967

Under new Fairchild management in the 1970s, Harry’s international expertise found him involved in a variety of high-level sales, technology licensing, and manufacturing projects. He negotiated agreements with state-owned and private companies, including those in Austria, China, Hungary, and Russia. Wilfred Corrigan, Fairchild president from 1974 to 1979, said, “Harry was very comfortable with this position influencing new relationships at a time that very few people at Fairchild had much visibility outside the US.”

Harry retired from Fairchild, by then owned by Schlumberger, in 1981. He formed a consulting company specializing in international licensing and technology transfer. This required frequent trips to Washington, DC, where he engaged in several hotel elevator conversations with Robert Redford during the filming of All the President’s Men.

With Hans Queisser, Jim Gibbons, and Jay Last at Shockley Labs 50th anniversary celebration, 2006

Beginning in 2005, Harry and I worked together again at the Computer History Museum in Mountain View. As director of the Semiconductor Special Interest Group (Semi SIG), I found his breadth of experience and strong relationships with pioneers of the industry extremely valuable. At age 91, Harry trained and donned the Museum docent shirt and enjoyed regaling young audiences with inside stories of the history of the technological revolution that he had lived.

A celebration of life for Harry Sello will be held at the Computer History Museum in Mountain View on Saturday May 27, 2017, at 10:30 a.m.

If you have a memory you’d like to share of Harry Sello, please email us here.