CHM now has a virtual presence in Minecraft: Education Edition. The Great Tech Story is a new “world” in the popular game platform that’s designed to help teachers prepare students to become knowledgeable and ethical users and builders of technology. In partnership with veteran world builders ReWrite Media, CHM curators and museum educators mined the collection for fun objects and diverse and interesting people to populate the game world.

It’s fair to say that neither the CHM team nor the game development team fully understood what it would take to make this brave new world.

Although some of us have experience creating curriculum and interactive activities for students at the Museum, no one on the CHM team had ever developed a game before.

As we let our imaginations roam—often wildly and unproductively—the ReWrite team’s patience, positive attitude, and can-do spirit never wavered. Even when we asked for the seemingly impossible, they came up with ingenious solutions, creatively working to realize our vision in Minecraft’s blocky, pixelated environment.

The CHM lobby in the Minecraft game.

Slow, clumsy users ourselves, we were awed by the speed with which our partners zipped around the world, often building new features in real-time during meetings. Working with new people who shared our vision of CHM as a great place for learning and fun was Senior Curator Dag Spicer’s favorite part of the project.

Though we all love technology, I was struck by the different work cultures of a museum and a game development company. They move fast and try things out to see if they work. We move more slowly, trying to imagine the future implications of decisions before we make them. But we discovered we’re equally obsessed with detail.

An example of the developers’ notes on some changes made to the game.

Kate McGregor, director of education at CHM and the team lead for the game, noticed that there were posters of skulls on the walls of the virtual Museum. When she asked about it, the developers laughed. It’s a poster they put in all their Minecraft worlds and without thinking they’d added it to CHM. They replaced it with more appropriate artwork, like the ones below.

Art on the walls in the exhibit showing AR/VR goggles and an early website for the White House.

As a content developer and writer, the 256-character limit for panels in the game was particularly challenging for me. We had to work hard to distill big ideas and lots of information into text that would engage student players. It was an interesting exercise, particularly for the curators on the team, who could (and have) written whole articles and books about what we were trying to share.

ReWrite designer Ryan Meuer worked on recreating the physical building using reference photos. For him, designing the game layout in a way that both resembled the layout of the real CHM exhibit, Revolution: 2000 Years of Computing—notorious for its complexity—and making it easy to navigate was a challenge. It’s unique in Minecraft to have something detailed and true-to-life that’s so close to scale, he said, and he enjoyed learning about and seeing each artifact come to life.

A section of the exhibit in the game showing a magnetic disk storage device and an Incan quipu, an ancient device for storing data with knots and thread.

The CHM team had to determine which artifacts from the thousands on display and in our collection to use that would help us share lessons and be fun for students to learn about. Oh, and that could also be recreated in Minecraft.

Those artifacts include the 2000-year-old Antikythera mechanism—the oldest known scientific calculator—the Apollo lunar lander, handheld precursors of the smartphone, and a self-driving car. CHM’s Kate McGregor was excited to see her favorite artifact, Shakey the Robot, brought to life in digital form to reach a larger audience.

Shakey the robot in the Minecraft CHM exhibit.

Kip Spangler, a ReWrite artist and designer, was intrigued about how things like the IBM 1401 changed and innovated computation and showed him how far computers have come today. The Cray-1 Supercomputer, which featured a central column surrounded by a padded, circular seat, was a hit with the game developers. ReWrite Mechanic Christopher Childress’ said, “It’s a shame computers don’t come with their own upholstery anymore.” For ReWrite Project Manager Allison Bondoc, the Cray-1 is the number one artifact she wants to visit in the real Museum.

The Cray-1 computer in the Minecraft CHM exhibit.

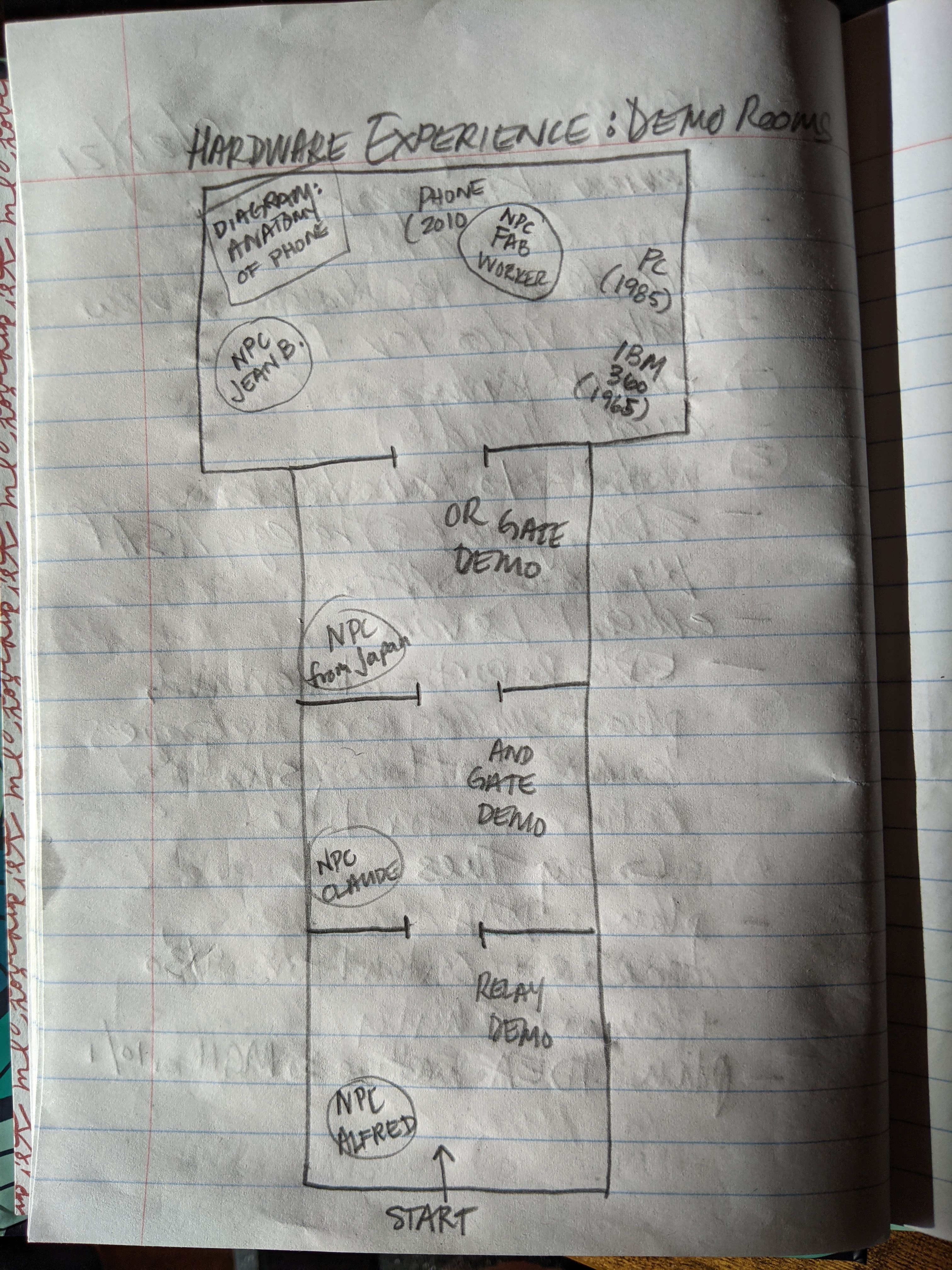

As students navigate the exhibit, they meet “non-player characters (NPCs)” who share information about the artifacts and concepts they’re encountering. NPCs include historic figures and still-living computing pioneers as well as a diverse group of tech users and innovators. With accessibility a deep concern for both teams, CHM consulted with disability experts and the developers created a Minecraft NPC using a power wheelchair with voice command tech.

This NPC, a high school student named Antonio, appears in an immersive learning experience where a family demonstrates how they use technology in daily life.

“The sheer number of interactable NPCs with unique dialogue is certainly higher than any previous projects I’ve worked on,” noted Christopher Childress.

The CHM team chose familiar NPCs like Alan Turing and Admiral Grace Hopper as well as lesser-known figures like Elizabeth “Jake” Feinler, who played a key role in the early internet, and Claude Shannon, who appears in a tuxedo to convey period clothing from the 19th century.

Claude Shannon stands beside a demo about relays in the Hardware Garage.

“Since the visual palette is so simple (8-bit blocky appearance),” said CHM’s Dag Spicer, “I enjoyed the back and forth between curators and developers with how to distill an historical character’s essence for the game within these limitations.” His favorite character is Margaret Hamilton, who created software for the Apollo mission that landed men on the moon.

NPC Margaret Hamilton stands beneath the Apollo lunar lander.

For Kip Spangler, Ada Lovelace was the favorite. “Before getting to work on the CHM Minecraft World, I hadn’t gotten the pleasure of learning about her,” he said.

Students meet additional NPCs and learn more in-depth concepts when they’re teleported from the exhibit to five immersive learning experiences. They’re introduced to the basics of computing technologies, programming concepts, the entrepreneur’s journey, ethics in tech, and the impact of tech on daily life.

An early diagram for the activities in the Hardware Garage immersive experience.

The game developers were instrumental in repurposing Minecraft’s medieval-esque tools and features into activities that teach technological concepts. For example, to learn how punched cards can tell computers what to do, students use a pickaxe to smash squares in a giant card. When they succeed in “punching” the hole, a related “furnace” lights up.

Punched card activity in the immersive Software Lab experience.

I’m terrible at wielding the pickaxe, but the game developers assured me it’s a basic skill for anyone who plays Minecraft and the students will have no trouble using it, or any of the other tools they’ll need to tackle the game’s culminating “build challenge.”

Though humbling, I’m reminded that we all have something to teach each other: curators and educators, game developers and coders, and, most importantly, who we’re doing it all for—the kids who’ll become the next generation of technology innovators.